Unemployment insurance was a major element of the U.S. government’s response to the economic dislocation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, enacted in March 2020, expanded the unemployment insurance system to provide relief to those who were out of work. Subsequent legislation extended these benefits until September 6, 2021.

Created in 1935, the federal-state unemployment insurance (UI) program, as it was structured pre-COVID-19, temporarily replaces a portion of wages for workers who have been laid off, as long as they are looking and available for work. Although benefits vary by state, in most states the program provides up to 26 weeks of benefits to unemployed workers and, in most states, replaces 30 percent to 50 percent of a worker’s previous wages. Because more workers lose their jobs during economic downturns, this program also provides needed economic stimulus that helps mitigate the severity of recessions.

Initial claims are the number of new applications filed by individuals seeking UI benefits—one indication of the health of the job market. In early April 2020, initial claims for UI benefits surged to roughly 6.2 million in a single week—their largest level on record—because workplaces were shut by lockdown measures put in place to slow the spread of coronavirus. The previous high was 695,000 claims filed the week ending October 2, 1982.

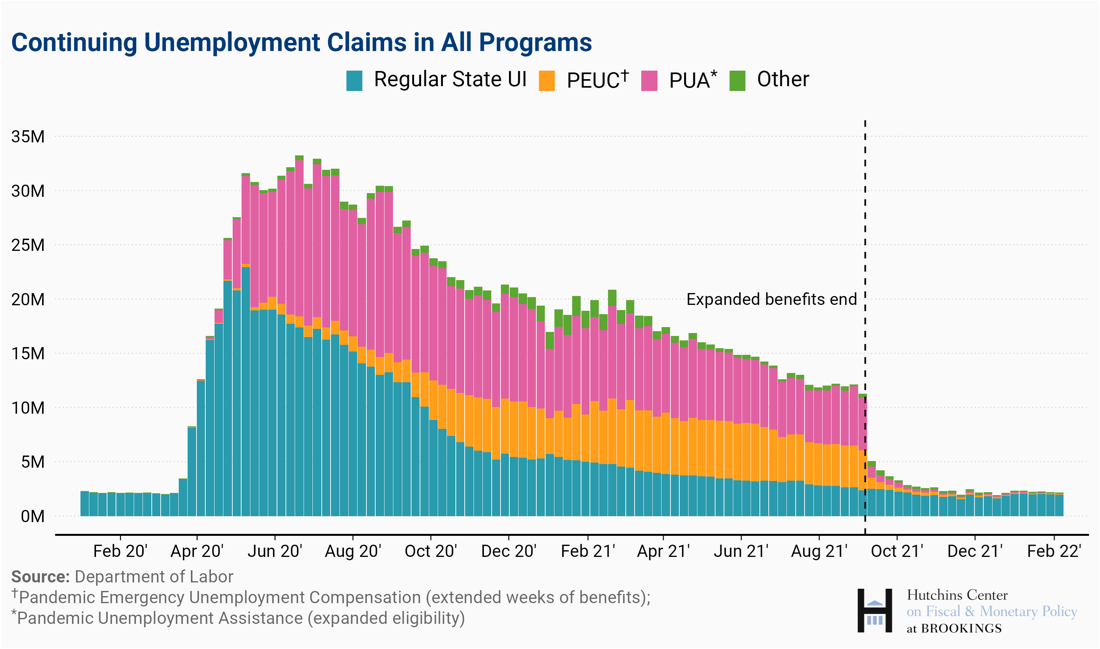

The total number of workers collecting unemployment benefits (often called “continuing claims”) peaked at 33 million, or roughly one in every five people in the labor force, during the week ending on June 20, 2020. This included more than 15 million people who were collecting benefits under pandemic-related expansions of the program. Total continuing claims have declined sharply since then. In the week ending February 5, 2022, they stood at 2 million.

The regular UI program is funded by taxes on employers, including state taxes (which vary by state) and the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) tax, which is 6 percent of the first $7,000 of each employee’s wages. However, employers who pay their state unemployment taxes on time receive an offset credit of up to 5.4 percent, meaning that the FUTA tax for an employee earning $7,000 or more may be as little as $42. The credit is reduced in states that are overdue in repaying unemployment insurance debt owed to the U.S. Treasury.

States have extensive flexibility in determining benefits. Federal requirements are minimal, while ensuring that all states provide basic protection for eligible workers. States are free to choose the level of employer tax, the benefit level and duration of benefits, and the eligibility criteria, such as the extent and duration of prior employment. There is considerable variation in how states run this program. For instance, while the standard maximum time for which eligible people can collect benefits is 26 weeks, when the COVID-19 crisis began in late February 2020, states like Florida and North Carolina were limiting state-paid benefits to just 12 weeks.

While state spending on UI is not subject to balanced budget rules and states can borrow from the Treasury if they exhaust their reserves, they have to repay the federal government within two to three years, or federal taxes on employers automatically increase until the debt is paid.

Twenty-two states borrowed from the federal government to pay for UI benefits in 2020. While federal pandemic unemployment loans were initially interest-free, states started paying a 2.3% interest rate on their outstanding debt when the federal UI expansion ended on September 6th, 2021. Some states, like Ohio and Nevada, tapped into their funds provided by the American Rescue Plan to pay off their loans in full and avoid paying interest.

However, ten states failed to repay their loans before interest started accruing, and collectively owed the federal government $40 billion as of February 28, 2022. Absent repayment or elimination of outstanding unemployment loans by November 10, 2022, employers’ federal UI taxes will also increase for wages paid in 2022.

Most state UI systems replace 30-50 percent of prior weekly earnings, up to some maximum. Before the expansion of UI during the coronavirus crisis, average weekly UI payments were $387 nationwide, ranging from an average of $215 per week in Mississippi to $550 per week in Massachusetts. Since payments are capped, UI replaces a smaller share of prior earnings for higher-income workers than lower-income workers. While program formulas vary significantly, states that have higher maximums tend to have higher replacement rates. In the fourth quarter of 2019, Hawaii’s average replacement rate of 54 percent was the highest; Arkansas’s average replacement rate of 31 percent was the lowest.

No. In ordinary times, most unemployed workers don’t receive UI benefits. UI does not cover people who leave their jobs voluntarily, people looking for their first jobs, and people reentering the labor force after leaving voluntarily. Self-employed workers, gig workers, undocumented workers, and students traditionally aren’t eligible for UI benefits.

In addition, most states require unemployed workers to have worked a minimum amount of time or received a minimum amount of earnings from their previous employer to be eligible. The minimum amount of earnings required to qualify for UI benefits ranged from $1,000 to $5,000 in 2019. Due to differences in eligibility criteria, the UI recipiency rate—the portion of unemployed people who receive UI benefits—varies significantly across states. In the fourth quarter of 2019, Mississippi’s 9 percent recipiency rate was the lowest; Massachusetts’s 55 percent rate was the highest.

Another consequence of earnings and work history requirements is that low wage workers—who are most likely to become unemployed—are among the least likely to get UI benefits. During the Great Recession, only one quarter of low-wage workers—defined as those who earned less than their state’s 30th percentile wage—received UI benefits when they became unemployed. Workers who earned more than the 30th percentile wage before becoming unemployed were twice as likely to receive UI benefits. The main reason low-wage workers do not qualify for unemployment benefits is not low hourly wages per se. Rather, low-wage workers also tend to work intermittently, and most states require laid off workers to have minimally steady earnings over the previous year to qualify for the maximum number of weeks of benefit payments.

What did Congress do during the pandemic crisis?

During past recessions, Congress funded additional weeks of UI benefits for those who exhausted their regular state benefits. This time, it did more.

The Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) program added $600 per week to state-funded unemployment benefits, financed by the federal government. That expansion expired on July 31, 2020. In December 2020, Congress voted to provide expanded benefit payments of $300 per week through March 12, 2021. The American Rescue Plan (ARP) extended that $300 per week increase in unemployment insurance payments until September 6, 2021. The ARP also exempted the first $10,200 in unemployment benefits received in 2020 from taxation, but only for those whose income was below $150,000.

The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program extended benefits to previously ineligible workers including part-time workers, freelancers, independent contractors, and the self-employed. This provision expired on September 6, 2021.

The Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program extended the duration of UI benefits by 13 weeks beyond the maximum provided by each state. This provision was set to expire on December 31, 2020; however, in December 2020, Congress extended the PEUC through March 14, 2021 and increased the number of weeks that workers could claim PEUC benefits from 13 to 24 weeks. The ARP extended the PEUC to September 6, 2021, and increased the duration of benefits to 53 weeks. This provision has also expired.

Twenty-six states withdrew pandemic-era jobless support before the September 6, 2021 expiration of the federally-funded extra benefits, arguing that the benefits were dissuading people from returning to work. There were 5 million people receiving jobless aid as of September 11, down from 11.3 million the week prior—the largest cutoff of unemployment benefits in history.

In addition, the ARP allocated $2 billion to modernize the IT system and make the UI system easier to access, better prepared to prevent fraud, and more resilient to prepare for future surges in initial claims. This investment is in response to a major problem with the UI system that emerged during the COVID-19 crisis: state labor offices with outdated computer systems were overwhelmed by the volume of claims. Andrew Stettner, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, estimates that by the end of May 2020, only about 18.8 million out of 33 million claims (57 percent) had been paid nationwide, an improvement from 47 percent of claims at the end of April and just 14 percent at the end of March of 2020. For people who rely on UI to meet basic needs, waiting weeks or even months to get their checks creates many hardships, even though the benefits are retroactive to the time of filing.

According to researchers at the University of Chicago’s Becker Friedman Institute, about two-thirds of workers were making more from UI during the pandemic-linked expansions than when they were working. One out of five eligible unemployed workers received benefits at least twice as large as their lost earnings.

Some argue that tight labor markets reflect, at least in part, the generous unemployment insurance benefits that allowed people to stay out of the labor market. But the evidence suggests that this effect has been small. Peter Ganong from the University of Chicago and coauthors estimate that the $600 supplement reduced employment by less than 0.8%, and the $300 supplement reduced employment by less than 0.5%.

Research by Kyle Coombs of Columbia University, Arindrajit Dube of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and co-authors found that in June 2021, 22 states ended benefits entirely for 2 million workers and reduced benefits by $300 a week for more than 1 million workers. Comparing labor markets in those states to states that retained the federal benefits, they found that earnings from work rose by only $14 per UI recipient per week in states that cut off benefits, but weekly UI income fell by $278. Because of lower total incomes, UI recipients spent $145 less weekly. In the 19 states analyzed, that translates to a $2 billion drop in spending and a $270 million increase in earnings from June through early August.

Overall, employment hasn’t grown any faster in states that withdrew from the UI programs early than in the ones that continued them into September. Looking forward, Coombs and Dube estimate that the end of UI benefits will lead half a million workers to get jobs between October and November 2021. Goldman Sachs predicts the cessation of benefits for 5.3 million people (roughly 2.7 million of whom earned more from UI than they earned in their last job) in September 2021 will add 1.3 million jobs by the end of the year. As of October 2021, there are five million fewer people working than in February 2020.

Several proposals have been advanced in recent years to reform the UI system. These include proposals to:

Labor & Unemployment Unemployment insurance is failing workers during COVID-19. Here’s how to strengthen it

Annelies Goger, Tracy Hadden Loh, Caroline George

Los Angeles skyline after California issued a stay-at-home order as the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues, in Los Angeles, California, U.S., April 3, 2020. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson" />

Los Angeles skyline after California issued a stay-at-home order as the spread of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues, in Los Angeles, California, U.S., April 3, 2020. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson" />

Labor & Unemployment Labor market in March deteriorated much more quickly than the unemployment rate suggests