February 2021

The National WIC Association (NWA) is the non-profit voice of the 12,000 public health nutrition service provider agencies and the over 6.3 million mothers, babies, and young children served by the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC). NWA provides education, guidance, and support to WIC staff; and drives innovation and advocacy to strengthen WIC as we work toward a nation of healthier families. For more information, visit www.nwica.org.

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF), founded in 1930 as an independent, private foundation by breakfast cereal innovator and entrepreneur Will Keith Kellogg, is among the largest philanthropic foundations in the United States. Guided by the belief that all children should have an equal opportunity to thrive, WKKF works with communities to create conditions for vulnerable children so they can realize their full potential in school, work and life.

The Kellogg Foundation is based in Battle Creek, Michigan, and works throughout the United States and internationally, as well as with sovereign tribes. Special attention is paid to priority places where there are high concentrations of poverty and where children face significant barriers to success. WKKF priority places in the U.S. are in Michigan, Mississippi, New Mexico and New Orleans; and internationally, are in Mexico and Haiti. For more information, visit www.wkkf.org.

Berry Kelly, MBA

Chair

Director, Bureau of Community Nutrition Services South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control

Sarah Flores-Sievers, BS, MPA

Chair-Elect

WIC and Farmers Market Director

Public Health Division/Family Health Bureau New Mexico Department of Health

Beth Beachy

Chair Emeritus

Director, Birth to Five Division

Tazewell County Health Department, Illinois

Meaghan Sutherland, MS, RD, LDN, CLC

Secretary

Nutrition Education Specialist, WIC Program Massachusetts Department of Health

Melinda Morris, MS, RDN, IBCLC

Treasurer

WIC Program Manager

Boulder County Public Health, Colorado

Douglas Greenaway, MARCH, MDIV

President & CEO National WIC Association

Stephanie Bender

Nutrition Coordinator

Bureau of Women, Infants, and Children Pennsylvania Department of Health

Sarah Bennett

WIC Director

Buncombe County, North Carolina

Samantha Blanchard Nutrition Coordinator WIC Nutrition Program

Maine Department of Health and Human Services

Regina Brady

WIC Director

Thames Valley Council for Community Action, Connecticut

Sarah Brett, MS, RDN Nutrition Coordinator Oregon WIC Program

LaKeisha Davis

WIC Director

Swope Health Services, Missouri

Karen Flynn

WIC Director

Vermont Department of Health

Kate Franken, MPH, RD

WIC Director, Child and Family Health Minnesota Department of Health

Mitzi Fritschen, MEd, RD, LD

WIC Branch Chief

Arkansas Department of Health

Paula Garrett, MS, RD

Director, Division of Community Nutrition Virginia Department of Health

Angela Hammond-Damon, IBCLC e-WIC Project Deputy Director Division of Health Promotion Georgia Department of Public Health

Rhonda Herndon, MS, RD/N, LD/N Bureau Chief, WIC Program Services Florida Department of Health

Beth Honerman

Nutrition Coordinator

South Dakota Department of Health

Robin McRoberts, MBA, MS, RD

Director, Community Programs

Visiting Nurse Association of Central Jersey, New Jersey

Carol Raney

Nutrition Coordinator

Indiana State Department of Health

David Thomason

Director, Nutrition and WIC Services

Kansas Department of Health and Environment

Paul Throne, DrPH, MPH, MSW Director, Office of Nutrition Services Prevention and Community Health Washington State Department of Health

Jody Shriver

WIC Project Coordinator, Muskingum County Zanesville-Muskingum County Health Department, Ohio

Laura Spaulding, RDN

WIC Supervisor

Deschutes County Health Services, Oregon

Tecora Smith

WIC Director

Northeast Texas Public Health District, Texas

Christina Windrix

Nutrition Coordinator

Oklahoma Department of Health

It would be an understatement to say that WIC is the nation's premier public health nutrition program. Decades of evidence-based research and reviews confirm that well-earned recognition.

To America's families, though, WIC means so much more than science-based outcomes. To them, WIC is a safe and welcoming home where there is no shame or blame, where we share the joys and anxieties of parenting, where we celebrate with delight new babies and growing young children, and where we honor with pride moms and dads doing their best for their families. It is where families receive dependable health, nutrition, and social supports and guidance generously offered with love and care to the families we assist. With certainty, WIC families know that WIC is a hand up in the midst of a world of uncertainty.

For these reasons and many more, we are proud to share with you this inaugural State of WIC Report. It is published to help you appreciate the scope and depth of WIC services and our active engagement with families and communities. It is offered to share our gifts and strengths and to highlight our opportunities for growth. It is replete with recommendations to enhance the value and quality of WIC services. Why? There is so much more that we can do as public health nutrition experts and as a nation to transform lives and help our country continue to bend the moral arc of the universe towards health equity and justice.

Two essential traits that we invite you to know about WIC staff: We fall in love with the work that we do because we know we are making meaningful differences in the lives of the families we support; and second, we fall in love with the families we serve. So many of us dedicate our entire professional careers to being present for our young families. We are committed to helping them discover the importance of healthy nutrition, to buoy their health and wellbeing, and to helping them find their footing for their life's journey.

It is in that spirit of dedication and love of all things WIC that we offer this State of WIC Report as a blueprint for action to help make WIC even more responsive to the needs of mothers, dads, babies, and young children.

We are confident that you will agree with us that there are no Red or Blue babies and young children, only the faces of our nation's future. When we reach, teach, and keep families engaged with WIC, we know that their futures as individuals and families are healthier and brighter, and our future as a nation is healthier and brighter, too. We hope that this State of WIC Report will inspire you to action to help us strengthen WIC for all of our futures.

Yours Sincerely,

National WIC Association

Since 1974, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) has provided healthy food, quality nutrition services, breastfeeding support, health screenings, and healthcare and social services referrals for millions of expectant and new parents, babies, and young children. Administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), WIC's targeted, time-limited services are demonstrated to improve birth outcomes and support positive child growth and development, helping to grow a healthier next generation.

WIC stands at the intersection of food security and public health. First established to address the pernicious effects of early childhood malnutrition, WIC is distinguished from other federal nutrition programs through its integrated public health services and health screenings. These complementary supports are critical in achieving the improved health outcomes that set up WIC babies and young children for future life success. Since passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which reoriented the healthcare system toward preventive services, WIC's successful nutrition intervention and established rapport with families have been increasingly leveraged to address systemic national health concerns, including childhood obesity, diabetes prevention, maternal and infant mortality, opioid and substance use, and lead exposure.

This inaugural report on the state of WIC services recognizes that the program stands at a crossroads. Comprehensive reform and targeted investment are needed to modernize WIC's twentieth-century service delivery for new generations of twenty-first century expectant parents. Even in its earliest proposals, the Biden-Harris Administration has recognized this need with a call for $3 billion in multiyear investments for enhanced benefits, stronger outreach efforts, and program innovations. With necessarily amplified attention on the nation's persistently poor maternal and infant health outcomes, increasingly driven by sharp and systemic racial and ethnic disparities, streamlined access to WIC services can work in tandem with broader healthcare reforms to ensure that all children in the United States are afforded a healthy start.

Expand program access to address nutrition gaps. WIC’s effective nutrition intervention is demonstrated to improve dietary quality and access to healthy foods, prevent or mitigate chronic diet-related conditions, and strengthen subsequent pregnancy and child health outcomes. WIC should provide ongoing nutrition support until a child is eligible for the National School Lunch Program by extending eligibility to age six or the beginning of kindergarten. WIC should also improve overall adult health during the inter-pregnancy interval by extending postpartum eligibility to two years for both breastfeeding and non-breastfeeding participants. WIC’s public health services are also critical for the families of those serving in our armed services, and expanded access for military families could help prepare the next generation of servicemembers.

Strengthen the nutritional quality of WIC-approved foods. NWA led a decades-long effort to partner with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) to align the available WIC food packages with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, offering science-based healthier options to families to positively address childhood obesity and other diet-related trends. 1 Increasing the value of the WIC food packages in a manner consistent with the 2017 NASEM recommendations will enhance access to fruits and vegetables, increase flexibility in the food packages to promote continued breastfeeding, and improve the overall dietary quality of WIC families.

Streamline certification processes. The annual certification appointment, which includes burdensome paperwork requirements, is one of the principal barriers to ongoing WIC participation. USDA has identified a 21 percent drop in coverage of eligible children at the one-year mark, and participation continues to decline until only one-fourth of eligible four-year- olds are certified in the program. 2 Clinic processes could be streamlined by extending certification periods to two years, making permanent a COVID-19 flexibility that would extend certification periods for up to three months to promote family alignment, and enhancing partnerships with early childhood providers by waiving the income test through adjunctive eligibility with Head Start, FDPIR, and CHIP.

Enable remote certifications. State-based waivers issued through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act permitted most WIC providers to implement remote certification appointments throughout COVID-19. Although a necessary measure during a pandemic, remote appointments are a significant step forward in reducing barriers to access, such as transportation, reconciling work schedules, and arranging childcare. The statutory physical presence requirements should be altered to permit video certifications and allow for telephone appointments when there is a barrier to access.

Invest in WIC technology infrastructure. WIC providers made a significant technological advance by implementing electronic-

benefit transfer (EBT), or e-WIC, transactions nationwide, and State WIC Agencies continue to innovate new service-delivery models to streamline the clinic and shopping experiences. By establishing annual funding for technology and Management Information Systems (MIS) grants, WIC could integrate new projects into their clinic computer networks, enabling innovations like web-based participant portals, prescreening tools, text-messaging features, and additional transaction models like online purchasing and mobile payments. 3

Streamline WIC access to electronic health information. Families raising young children should have consistent access to health information from both their physician and WIC provider, enabling accurate growth charts and reducing

duplicative tests for young children. A joint USDA-HHS project to streamline electronic health information sharing between WIC providers and physicians would be a significant step forward in streamlining patient data and integrating WIC into a family’s overall healthcare experience.

Invest in WIC referrals and partnerships. As a critical point-of- contact, WIC plays an essential role in connecting families with healthcare services. Ongoing efforts to refer out from WIC should be enhanced by increased referrals to WIC, which will help connect the nearly 7 million eligible people who are not certified for WIC services.4 Dedicated funding to support local referral networks with physicians and state-driven data projects with Medicaid, IHS, and SNAP would strengthen WIC participation, reducing overall healthcare expenditures. Additional funding for WIC’s Breastfeeding Peer Counselor Program would support out-of-clinic placements with physicians, hospitals, and home visiting programs to deliver targeted breastfeeding support for new mothers.

Strengthen WIC funding for public health services. WIC’s nutrition education and breastfeeding support are critical parts of assuring improved health outcomes, but they are consistently underfunded by an outdated funding formula that allocates resources to State WIC Agencies. Over the past decade, flaws in the funding formula have exposed this underinvestment, with WIC limited by regulatory barriers that prevent the program from strategically investing resources in these critical services.

Thoughtful flexibilities to increase WIC’s Nutrition Services & Administration (NSA) grant would assure investments in the wide range of nutrition services and related technology improvements needed to shape positive health outcomes in the current and next decade.

Leverage the WIC workforce to address chronic disease across populations. WIC’s professional staff of Registered Dietitians (RDs) and credentialed lactation consultants are trained and have the skills to provide a range of clinical healthcare services, including diabetes prevention, medical nutrition therapy, and lactation support. To further WIC’s documented health and nutrition success, Congress and the Administration should empower integrated healthcare services that bill to Medicaid, private health plans, and WIC to provide a full range of clinical nutrition services and breastfeeding support to both WIC participants and other families.

Modernize the WIC shopping experience. The rapid escalation of the SNAP online purchasing pilot has demonstrated the critical need to invest in WIC transaction models — including online purchasing, online ordering with curbside pickup, self-checkout, and mobile payments. These necessary technology innovations must also be paired with in-person supports at retail grocery stores to assist WIC participants with navigating the shopping experience and aid newly hired cashiers.

Address racial disparities in maternal health. Black and Indigenous women are more likely to face negative pregnancy outcomes — including a higher rate of mortality — than other racial and ethnic groups.5 Expanding access to WIC’s effective interventions can improve pregnancy outcomes overall. Anti- racism trainings for the WIC workforce and efforts to diversify the nutrition and lactation support fields can address the systemic racism in public health. The Administration should also reverse the public charge rule and take additional steps to assure that immigrants and mixed-status families have access to healthcare and other federal supports.

Support tribal administration of WIC services. WIC provides the option for tribes or inter-tribal organizations to administer WIC services as a State WIC Agency, with 33 Indian Tribal Organizations (ITOs) currently operating. Additional ITO funding and regulatory flexibilities could enhance the long-term viability of ITO State WIC Agencies, with specific vendor reforms related to food sovereignty enhancing the capacity of WIC to respond to historic inequities

in agriculture, food production, and food access for Indigenous communities.

Resolve barriers to women’s economic security. WIC’s public health nutrition supports would be a beneficial service for families of any income, but 65 percent of current participants live below the federal poverty line. 6 Nutrition works in tandem with other factors — including investment in childcare, household income, workplace conditions, and access to healthcare — to assure positive pregnancy outcomes. WIC participants benefit when policymakers strengthen protections for and invest in women’s economic security.

WIC PARTICIPATION REDUCES THE PREVALENCE OF CHILD FOOD INSECURITY BY AT LEAST 20 PERCENT. 7945%

NEARLY HALF OF ALL INFANTS BORN IN THE UNITED STATES PARTICIPATE IN WIC 7

$2.48

EVERY DOLLAR SPENT ON WIC MORE THAN DOUBLES THE RETURN ON INVESTMENT 8

For over forty-five years, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) provides time-limited services that are a crucial investment to ensure children get a healthy start. Decades of research and data collection into WIC outcomes demonstrates the positive impacts of WIC participation. WIC is an effective intervention that supports overall maternal health, healthy birth outcomes, and positive child growth and development.

WIC served nearly 6.4 million individuals in fiscal year 2019, the majority of which were children between ages one and five. 10 WIC reached over 1.6 million infants in fiscal year 2019, 11 which is estimated to be approximately 45 percent of all infants born in the United States. 12 WIC provides five core services to improve health and nutrition outcomes for participating families:

WIC provides a monthly benefit to purchase healthy foods that supplement the diets of WIC mothers and young children, with an average value of $40.90 per month. 13 There are seven core food packages, based on life stage and breastfeeding status, that are prescribed by WIC nutrition professionals and tailored to meet participants’ individual nutritional needs. 14 Although WIC is a breastfeeding promotion program, two food packages provide infant formula for partially breastfed and fully formula- fed infants. 15 WIC benefits, with few exceptions, can be redeemed at retail grocery stores by an electronic benefit transfer (EBT), or e-WIC, card. 16

WIC has the strongest nutrition requirements of any federal nutrition program, and the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 required an independent scientific review of the food package at least every decade. 17 The 2009 changes to the WIC food packages strengthened the nutritional quality of available WIC foods, including the introduction of a distinct Cash Value Benefit (CVB) that provides a small monthly benefit for the purchase of fruits and vegetables. 18

WIC provides individualized, participant- centered nutrition counseling that supports participants and their families in making healthy choices. Unlike other federal nutrition programs, WIC’s tailored nutrition education is core to the program’s mission. It provides a consistent touchpoint for WIC families to receive advice and support from nutrition professionals. WIC nutrition education takes various forms, from online modules to group classes to one- on-one counseling, either in person or via a telehealth platform. WIC nutrition educators — including Registered Dietitians (RDs), nutritionists, and other professionals — help families navigate their capacities, strengths, and needs to shape positive dietary behaviors.

As the nation’s leading breastfeeding promotion program, WIC provides individualized support, prenatal education, and access to breast pumps to encourage and strengthen a mother’s choice to breastfeed. Structural and societal barriers, such as a rapid return to work after delivery, lack of workplace supports for breastfeeding, family and social pressures, and targeted marketing by the infant formula industry, create real and perceived barriers for low-income mothers as they consider breastfeeding. 19 To help mothers overcome these significant barriers, WIC has built, over three decades, strong incentives to breastfeed — including the introduction of an enhanced food package for exclusively breastfeeding participants in 1992, 20 an extension of program eligibility for breastfeeding participants in 2004, 21 and critical investments in WIC’s Breastfeeding Peer Counselor Program in 2010 22 — all resulting in a 30 percent increase in breastfeeding initiation rates among WIC participants since 1998. 23

WIC eligibility is determined based on an assessment of nutrition risk, and WIC clinic staff routinely screen for height/ length and weight to measure adequate growth. WIC has a rigorous anemia screening protocol, to account for the higher rates of iron-deficiency anemia among the WIC-eligible population. 24 WIC’s anemia screenings are effective in tailoring nutrition-oriented interventions, with WIC infants now outpacing non-WIC infants in healthy iron intake. 25 For some families, these screenings have resulted in immediate life-saving medical interventions for vulnerable children. Select WIC agencies also partner with Medicaid to provide a range of other health screenings, including lead testing. 26

WIC screens for a range of other health factors and makes appropriate referrals, including for immunizations, tobacco cessation and substance use, prenatal or pediatric care, postpartum depression and mental health, dental care, and social services. WIC serves as a gateway to primary and preventative care, with the healthcare needs of children participating in both Medicaid and WIC found to be better met than low-income children who are not participating in WIC. 27 WIC participation is also associated with a higher likelihood of families showing up at well-child visits, 28 higher rates of childhood immunization than non-participating low-income children, 29 and higher rates of accessing dental care. 30

Prenatal WIC participation has a marked effect on the success of a pregnancy, especially for high-risk pregnancies. 31 Recent research associates WIC participation with a 33 percent reduction in the risk of infant death within one year of delivery. 32 Successful pregnancy outcomes are driven by the supplemental foods provided by WIC, which are tailored to increase intake of vital nutrients, including protein, folate, vitamin D, and iron. WIC’s nutrition support is vital in assuring healthy pregnancies by significantly reducing the risk of preterm birth 33 and low birthweight, 34 which are both associated with long-term health complications or infant mortality. 35

It is critical to connect pregnant participants with WIC services as quickly as possible, with over half of pregnant participants enrolling in their first trimester. 36 Maternal nutrition before and during early pregnancy can significantly impact fetal development and the child’s long-term health. 37 Maternal nutrition affects pregnancy outcomes both through micronutrient intake (e.g., folate intake affects the risk of neural tube defects 38 ) and chronic diet-related conditions such as obesity, high blood pressure, or type-2 diabetes. 39 Diet-related conditions like obesity are associated with several risk factors for maternal mortality, including preeclampsia 40 and cardiovascular conditions. 41 Since 39.7 percent of women in the United States between ages 20 and 39 have obesity, 42 WIC’s individualized nutrition counseling and support is a critical intervention to strengthen nutrition outcomes during pregnancy, mitigate pre-conception barriers to healthy pregnancies, and ensure adequate nutrition as participants plan for a subsequent pregnancy. 43

Dedicated program focus in promoting and supporting breastfeeding has led to a 30 percent increase in breastfeeding initiation rates for WIC infants since 1998. 44 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months, with continued breastfeeding as complementary foods are introduced through at least twelve months. 45 Over the past two decades, WIC has more than doubled the rate of breastfeeding at twelve months, 46 and WIC’s successful Breastfeeding Peer Counselor Program is associated with increases in the three key metrics of breastfeeding: initiation, duration, and exclusivity. 47 WIC support — including peer counselors — are effectiveat addressing racial disparities in breastfeeding rates, especially among Black women. 48

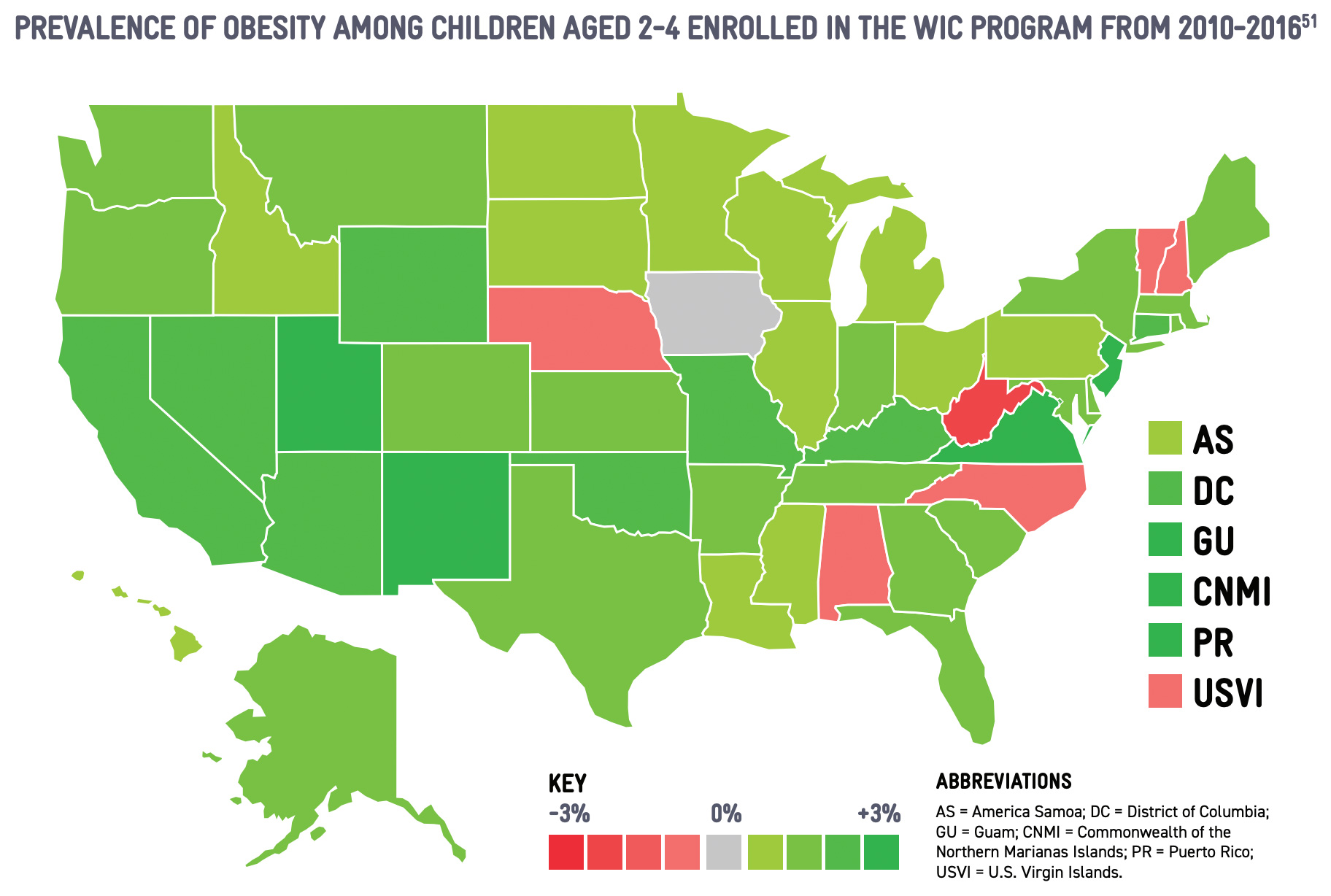

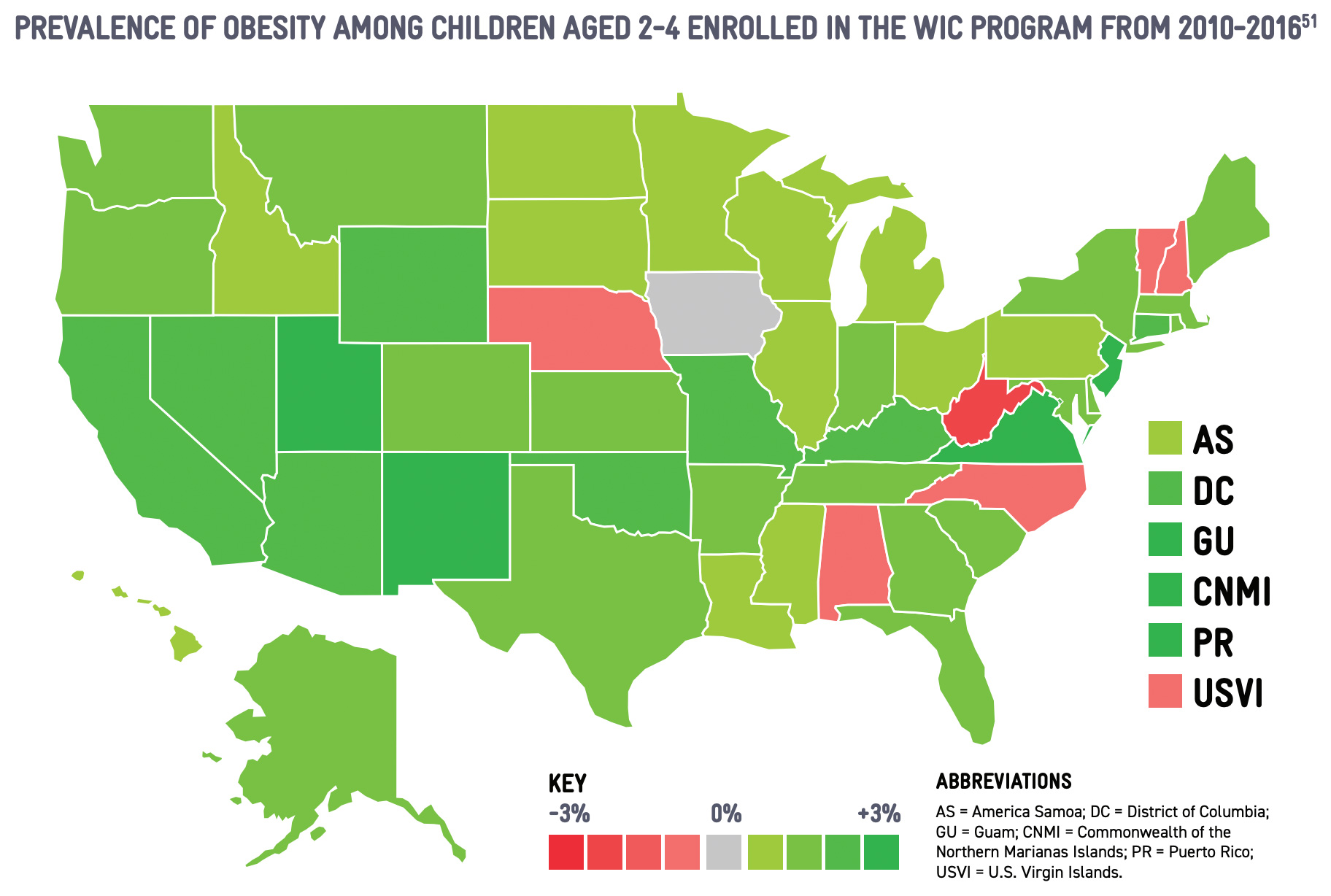

The National WIC Association promoted reforms to the WIC food packages in 2009 that have been instrumental in strengthening child nutrition outcomes for children ages one to five. A comprehensive analysis by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates decreases in the prevalence of overweight and obese children participating in WIC, from 32.5 percent in 2010 to 29.1 percent in 2016, in part due to the food package reforms. 49 The childhood obesity rate for WIC toddlers is now aligned with the national childhood obesity rate for children age two to five. 50

WIC participation is also associated with improved diet quality, 52 with children who have participated in WIC for their first 24 months of life scoring higher on the Healthy Eating Index. 53 Enhanced options in the child food package after 2009 are also associated with higher dietary quality, as a longitudinal study following over 1,300 WIC participants found that children who continue to participate in WIC after their first birthday have healthier diets than children who cease participation by the first birthday. 54 WIC participation is associated with higher consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains by participating children. 55

Although WIC's food benefit is issued as an individual prescription, the food benefit and WIC's complementary nutrition education can shape family dietary behaviors. Research indicates that WIC participation is associated with healthier purchasing habits by the family 56 and increased availability of healthy foods in retail grocery stores, especially smaller retailers. 57

Despite WIC's proven record of enhancing child nutrition, WIC eligibility ends on a child's fifth birthday. The majority of children do not enter school until at least age five-and-a-half, and are therefore not yet eligible for sustained nutrition assistance through the National School Lunch Program and National School Breakfast Program. 58

This gap exacerbates food insecurity for children as families must search for alternate sources for food, resulting in meals that do not account for the child's nutritional needs or the family skipping meals all together. 59 These new stressors can inhibit a child's growth at the onset of entering the education system, an unfortunate outcome given WIC's sustained role in improving cognitive development and academic performance among children. 60

The United States spends 17.7 percent of its Gross Domestic Product on healthcare, almost twice as much as other developed countries. 61 Despite this high spending, life expectancy in the United States is shorter, while the prevalence of chronic conditions is higher. 62 WIC is a strong federal investment, with recent research indicating that every dollar spent on WIC services returns at least $2.48 in medical, education, and productivity costs. 63 This analysis was limited to cost savings associated with preterm birth, suggesting that the program's total cost savings are actually higher. This finding builds on decades of research, including landmark studies from the early 1990s, demonstrating Medicaid cost savings associated with prenatal WIC participation. 64

Preterm birth and additional birth complications, including low birthweight, are associated with higher rates of infant mortality and significant health, cognitive, and developmental conditions. 65 Given the complexity of care for the first year after preterm birth, preterm births cost the United States over $26 billion each year, with average first-year medical cost estimated at $65,000 per infant. 66 Even small interventions can make a significant difference — an increase of one pound at birth for a very low birthweight baby can save approximately $28,000 in first-year medical costs. 67 WIC's effective nutrition intervention to assure healthy births ensures immediate healthcare cost savings by ensuring healthier birth outcomes, while also securing long-term savings by mitigating or preventing lifelong health conditions.

WIC's wide-ranging public health nutrition services reduce costs associated with additional healthcare efforts. Only 22 percent of infants in the United States are exclusively breastfed at six months as recommended. 68 WIC's breastfeeding promotion efforts are significant in increasing breastfeeding rates among low-income infants 69 and reducing racial disparities in breastfeeding. 70 National efforts to improve breastfeeding are associated with significant healthcare savings, with $9.1 billion in estimated savings if 90 percent of WIC infants were breastfed for their first year. 71

WIC's efforts to reduce childhood obesity have long-term effects on healthcare expenditures, as the additional incremental costs for medical care for each child with obesity is estimated at $19,000, 72 with overall annual medical costs in the United States estimated at $147 billion. 73 WIC also leads to additional Medicaid and healthcare cost savings, including lower dental-related Medicaid costs for participating children. 74

WIC has a direct economic benefit, channeling $4.8 billion in WIC food benefits to over 48,000 authorized retail grocery vendors in communities across the United States. 75 The majority of authorized stores are big box and larger retailers, but at least one-quarter of all WIC benefits are redeemed in small- and medium-sized stores. 76 Although smaller in reach than the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), WIC reforms to increase access to healthy foods in 2009 were associated with changes to store stocking practices, indicating that retailers will adapt to meet program requirements. 77 WIC's efficient cost containment efforts generated at least $1.7 billion in savings in fiscal year 2019, bringing in sufficient non-taxpayer revenue to support over one fourth of WIC participants. 78

As with the other federal nutrition programs, WIC has a proven record in reducing food insecurity rates and expanding household access to foods. 79 Early WIC participation can also help children succeed in school, with demonstrated associations between WIC participation, cognitive development, and academic success. 80 The cognitive and academic impacts of WIC are long-lasting, with the persisting effects throughout school-age years similar in magnitude to other early childhood interventions, including Head Start. 81

The federal child nutrition programs were first established to address military readiness and assure the civilian population was fit to serve. 82 The Department of Defense estimates that 71 percent of Americans aged 17 to 24 are ineligible for military service, 83 largely due to the increase in overweight and obesity. 84 Nutrition interventions for children from military families can be critical toward addressing national recruitment challenges, as parental service is a factor that may indicate future enlistment. 85

WIC provides targeted support to military families on some military bases through co-located clinics or mobile units, but WIC providers often note challenges in outreach to military families and navigating special income rules for military families. Over half of the approximately 72,000 infants born to military families each year 86 are currently eligible for WIC benefits. 87

Military families with young children report a level of food insecurity that is consistent with the civilian population, adding stressors that may be compounded as military spouses care for young children during deployment. 88 Enhanced access to WIC services for military families is a critical support and a meaningful investment in the country's future recruitment efforts.

![]()

![]()

WIC WAIVERS ARE APPROVED THROUGH 30 DAYS AFTER THE PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY DECLARATION 89

REMOTE APPOINTMENTS FUELED PARTICIPATION INCREASES IN THE MAJORITY OF STATES SINCE FEBRUARY 2020 90

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic presented one of the most significant public health challenges in WIC's history. WIC providers adapted rapidly by modifying services to provide continued support for expectant and new parents, infants, and young children while minimizing risk of exposure to COVID-19 to participants, clinic staff, and their families. WIC providers had to act quickly, as access to WIC services typically requires physical presence at community-based clinics. These sweeping changes in WIC service delivery, including reliance on telehealth strategies and flexibilities around certification, have profound implications for the program's future.

In mid-March, as public concern about the spread of COVID-19 reached a critical point, WIC providers began to reschedule appointments and close clinic doors. The immediate threat of the virus and the prospect of long-term social distancing raised complications, as WIC providers are required by federal law to conduct certain program operations in person — including onboarding new participants. 92 Without legislative action, WIC providers could not have been responsive to the needs of existing participants, let alone the surge of newly eligible families due to the pandemic's disruption to the national economy and job market.

Within days, Congress passed Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which included unprecedented waiver authority of statutory physical presence requirements and other regulatory barriers to access. 93 State WIC Agencies swiftly applied for and received critical, though conditional, waivers necessary to adapt services, including waivers of the physical presence requirement for new participants. 94 Physical presence waivers were paired with delays in requirements to conduct health screenings and assessments, including measurements of height/length, weight, and hemoglobin levels. Although the waivers allowed for increased flexibility and ongoing services during the pandemic, WIC providers were put in a similar position as healthcare providers — the delays in testing, screening, and referrals were leaving fewer children and families with the information necessary to assure optimal health. 95

With waiver flexibilities, WIC providers were able to adapt and provide uninterrupted services for families, but providers were quickly challenged by the short-term nature of waivers. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act vested USDA with waiver authority through September 30, 2020, 96 but USDA only approved waivers through May 31, 2020. 97 USDA's short-term approach created barriers for State WIC Agencies as they simultaneously budgeted to scale up technology to sustain remote services, sought consistency in messaging oriented at participants and retail partners, and planned contingencies in case USDA failed to extend the waivers.

About two weeks before the waivers were set to expire, USDA extended the waivers until June 30 and rolled out a process to require State WIC Agencies to resubmit waiver requests with additional justification. 98 The requirement to reapply for waivers caused substantial paperwork burden on State WIC Agencies in the midst of the pandemic and raised public health concerns, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) designated pregnant women as a population with increased risk of severe illness or adverse outcomes upon contracting COVID-19. 99 Under increased pressure, including a bipartisan letter from the Senate Agriculture Committee, 100 USDA extended the waivers without any further requests for justification through September 30, 2020, only one day before the waivers were set to expire. 101

In late September, USDA continued to delay a decision on extending WIC flexibilities. Less than two weeks before the waivers were set to expire, with pressure from the National WIC Association, Congress, and other stakeholders, USDA extended waiver flexibilities until 30 days after the expiration of the public health emergency declaration promulgated by the Secretary of Health and Human Services. 102 Additionally, Congress included an extension of USDA's authority to issue waivers in the continuing resolution that passed in late September, allowing USDA to issue new waivers through September 30, 2021. 103 This long-term solution provided the clarity that WIC providers would have relied on from the start of the pandemic, allowing for consistent messages to participants that strengthen outreach and support ongoing WIC participation during the public health crisis.

In March 2020, WIC providers swiftly implemented waiver flexibilities to ensure continued service for existing participants and onboard new families affected by the economic uncertainty related to the pandemic. The majority of State WIC Agencies instituted remote services, an effective and highly successful strategy to engage participants during the global pandemic. Initial evidence suggests that remote services are enabling increased participation, heightened engagement with existing participants, and greater flexibility and convenience for families. Building on earlier innovations to provide telephone or video conferencing for nutrition education, remote services are a success story of WIC efficiently adapting to meet the challenging circumstances of COVID-19.

Remote services are most practical in states that have already implemented electronic-benefit transfer (EBT), or e-WIC. In those states, since participants already have access to an EBT/e- WIC card, State WIC Agencies or local providers are able to remotely load benefits onto the card each month. Any other contact with WIC staff, including nutrition education and recertification appointments, could be handled by phone or video conferencing technology. In the few states that have not begun the EBT/e-WIC transition, the waiver authority allowed agencies to mail paper vouchers directly to participants' homes.

As of October 2020, two-thirds of states are reporting an increase in participation since February 2020. 104 The distribution among State WIC Agencies is uneven, with many states reporting increases between one and seven percent, and some states reporting double-digit increases ranging as high as 20 percent. This is a stark departure from prior trends, with WIC participation rates declining consistently since reaching a record high of 9.2 million in 2010 during the Great Recession. 106 WIC providers report that new participants include children who were previously certified but dropped off the program, families that were eligible before COVID-19 but not participating, and families that are newly eligible as a result of income loss during the pandemic.

There are two main indicators associated with the one-third of states that are still reporting declines in program participation. Over a dozen State WIC Agencies have offline EBT/e-WIC systems, which require that cards be manually reloaded at a clinic location. 106 Many offline WIC providers instituted curbside services, allowing participants to remain in their cars while clinic staff, garbed in personal protective equipment, would retrieve the EBT/e-WIC card and reload it at a distance. 107 USDA approved another set of waivers to allow benefit issuance for four months, instead of the more common three-month issuance, to reduce burdens on offline EBT/e-WIC states for both staff and participants. 108 Despite innovative strategies to reduce exposure, the majority of states that are still registering participation declines during COVID-19 have offline EBT/e-WIC systems. 109 Additionally, several states were rolling out EBT/e-WIC systems in the midst of the pandemic, causing confusion and disruption for participants. At least one state, Hawaii, demonstrated participation increases after the EBT/e-WIC transition was completed over the summer.

In addition to the physical presence waivers, thirty-five State WIC Agencies were granted short-term extensions of child certification periods for up to 90 days. 110 With WIC's health assessments delayed, there is little to distinguish a recertification appointment from more frequent nutrition education touchpoints. Short-term extensions of child certification periods are useful for reducing administrative burden on overworked WIC clinic staff and, in some cases, aligning child certification periods with other family members' certification periods. The waiver demonstrates the complexity of enabling remote certifications in a post- COVID environment, when measurements for height and weight and screening for hemoglobin levels will be required again. An essential part of enabling remote certifications in the long term will be enhanced coordination between physicians and WIC providers to facilitate information sharing and ensure that relevant health assessments are being conducted without duplication.

In March 2020, WIC participants reported increased challenges in navigating the shopping experience as the general public purchased excess groceries in fear of the pandemic and concerns about lockdowns or supply shortages. WIC's prescriptive food package limited the options for WIC shoppers, even if similar brands or products were otherwise available. WIC participants were increasingly concerned about shortages of WIC contract-brand infant formula, with some alarming reports in the first weeks of the pandemic around diluted or homemade formulas, which pose significant risks to infant health.

With passage of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, State WIC Agencies swiftly requested food substitutions for many prescribed WIC food items to enhance available options for WIC shoppers. Each State WIC Agency was granted food substitutions based on reported shortages in their state, leading to significant variations in waiver flexibilities across the country. Food substitutions were granted in nearly every food category, permitting additional package sizes and options. State WIC Agencies also independently reviewed their Approved Product Lists to add additional brands and products that were otherwise available.

For the most part, food substitution waivers were consistent with the nutritional integrity of the food package, with USDA denying State WIC Agency requests to provide products that did not meet the whole-grain requirements. The one exception was fat content in milk and yogurt, with USDA permitting fifty-six State WIC Agencies to allow milk products with any fat content and seventeen State WIC Agencies to permit yogurt with any fat content. USDA did not approve any substitutions for infant formula, as State WIC Agencies enter into sole-source contracts with manufacturers and negotiate rebate prices independent of USDA.

In the early weeks of the pandemic, USDA took steps to scale up the online purchasing pilot for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Authorized by the 2014 Farm Bill, the SNAP online purchasing pilot was already in the field when the pandemic worsened. USDA worked with Walmart, Amazon, and other retailers to rapidly escalate the pilot project to nearly all states. Although this action enhanced food access for millions of families, it exacerbated an inequity for WIC shoppers, who became the major population still required to conduct shopping in person. Although some stores have instituted special hours for pregnant shoppers and other at-risk customers, State WIC Agencies report that the disparity in transaction options between SNAP and WIC is having an effect both on participation and redemption of healthy WIC foods.

USDA was hesitant to issue waiver flexibilities that would empower innovation for new transaction models. Under existing regulations, WIC participants must redeem their benefits by signing or entering their PIN in the presence of a cashier. Despite several State WIC Agency requests, USDA did not approve a waiver of this regulation for three months. In July 2020, USDA announced a series of small-scale pilot projects for online ordering that would explore online purchases, although the pilot projects are not expected to be completed until at least 2023. In April 2020, in the absence of USDA engagement, the National WIC Association formed an Online Ordering Working Group comprised of WIC providers, retailers, EBT/e-WIC processors, and other stakeholders interested in exploring the steps necessary to operationalize safe transactions during COVID-19. Several promising models have emerged in recent months to strengthen self-checkout and build out online ordering systems that enable in-store or curbside pickup. The Working Group has also initiated conversations on the steps necessary to build out a system to enable WIC online purchasing.

WIC waiver flexibilities provided by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act ensure that services can continue uninterrupted, but additional steps could be taken to enhance the federal economic response to COVID-19. Food insecurity rates in households with young children doubled in the initial months of the pandemic, from 14 percent to 28 percent. 111

In January 2021, President Biden and Vice President Harris proposed a visionary investment of $3 billion in multi-year funding to strengthen WIC services, recognizing the program's importance in aiding families during the pandemic and resolving inequities during the nation's recovery. This funding would enhance food benefits, strengthen outreach, and drive innovation to modernize service delivery.

Enhanced benefits during the pandemic would complement efforts of SNAP and Pandemic-EBT to address the nation's worsening hunger crisis. WIC's Cash Value Benefit (CVB) allows for the purchase of fruits and vegetables, which had increased supply throughout the pandemic due to restaurant and school closures. The Biden-Harris proposal echos bipartisan efforts by Reps. Kim Schrier (D-WA) and Ron Wright (R-TX) to champion a short-term option that increases the value of the CVB in a win-win solution that supports WIC families and fruit and vegetable growers.